Teatro Anónimo Identificador: Popular Theater and Regional Identity in 20th Century Colombia

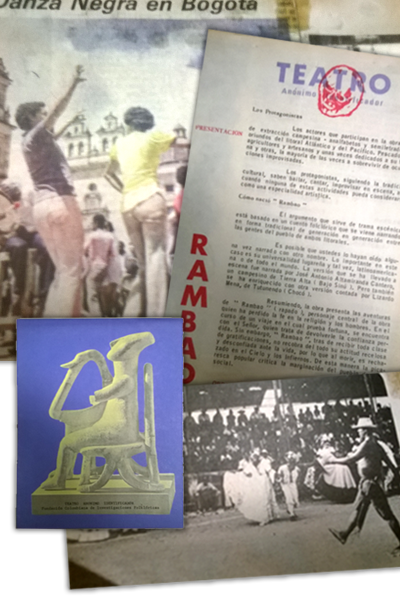

In the mid-1970s, Manuel Zapata Olivella and the Teatro Anónimo Identificador built on the deep traditions of street theater in Latin America by performing plays that showcased regional Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and mestizo rural culture.[1] Black Power and Negritud movements confronted a cultural context of black “invisibility” in Colombia during the 1970s.[2] The Teatro Anónimo Identificador and other theater companies in Colombia put black and indigenous culture and thought on proud display in the public sphere. They performed works grounded in the oral traditions, music, dance, and style of the popular classes in a given region. Admission was free and the shows were often held in open-air venues in the central plazas of towns and cities in order to attract large crowds. Zapata Olivella named it “teatro identificador” – theater that identifies. The group’s director, Fernando González Cajiao, described it as “theatrical experiment.”[3] Local people from the provinces of Córdoba, Meta, Arauca, and Boyucá rehearsed and performed these dramatic expressions of regional popular culture.

Zapata Olivella led the Fundación Colombiana de Investigaciones Folclóricos in conducting its theater project, with the goal of shaping black identity and advancing black power in Colombia during the 1970s.[4] Blackness entered the public sphere in striking ways in this period, and for his part Zapata Olivella utilized the channels of novels, television, radio, and theater to reach wide audiences. Land, territory, place, and region were crucial components in these projects and in the construction of black and indigenous identities in Colombia, reflecting a history of displacement, exclusion, and resistance. In the public performance of dramatic works, the Fundación highlighted the sights, sounds, rhythms, and oral traditions in regional peasant cultures.

Rambao Tour, 1975

By 1975 the Teatro Anónimo Identificador had two plays in circulation—one adapted to Atlantic and Pacific Coast regions, and the other to Colombia’s interior plains and Andean regions. They began performing Rambao in 1974, and the Grupo etnográfico contains transcripts and audio of interviews with people who attended the play during a period of several months in 1975. The Teatro Anónimo Identificador began its run in Zapata Olivella’s hometown of Lorica, Córdoba, with a performance of Rambao on March 19, 1975.[5] They then embarked on a tour of several towns in the Costeñ

o and Llanero regions of Colombia. The theater group performed the play in Montería, Córdoba on March 22,[6] and in Ayapel days later. They then took Rambao to the national capital of Bogotá in May 1975, before moving to Arauca in July, returning to Lorica in August, and concluding with a stint in the department of Boyacá in October.[7]

The black farmer, Filiberto Diaz, from Córdoba, played the lead character in Rambao, and the rest of the actors and performers were not “professionals” but ordinary people from the region.[8] Delia Zapata Olivella coordinated dance and music. González Cajiao, sociologists Raul and Gregorio Clavijo, researcher Roger Serpa, and filmmaker Alvaro González also played key roles in the preparation, production, and evaluation stages of the process. The team of researchers and artists spent several weeks in the region and conducted dozens of interviews seeking information on popular music, instruments, songs, stories, myths, food, work, relations between men and women, religion, and philosophy. “January 2, 1975 all of [us] were transplanted to Lorica,” González Cajiao recounted, “and [we] began the work that seemed like a challenge then, a theatrical adventure never before attempted, whose results were unpredictable.”[9]

The Teatro Anónimo Identificador’s production of Rambao was conceptualized as a process of helping to develop, display, and dramatize “eminently peasant” representations.[10] Black campesino life occupied center stage in this street theater, with a premium placed on “authentic” and unmediated local cultural expression. In pursuit of authenticity and spontaneity, Zapata Olivella insisted—over the objections of other team members—that no script be used and no memorization done. They worked from a “basic dramatic structure” from which they then improvised. González Cajiao wrote that they hoped that “memory, perception, wisdom and creativity, increasingly replace any kind of memorization or learning based on texts.”[11]

Regional Research Findings and Rambao’s Impact

The Teatro Anónimo Identificador team spent significant time and energy gauging the “impact” and reception of the play, anticipating the “results” it would achieve among the people. They developed a careful evaluation process that was set in motion immediately after the performance.[12] Researchers asked audience members their impressions of everything from where they thought Rambao should spend the afterlife, to which particular dance segment they most enjoyed. A diverse cross-section of Colombians who attended a performance told interviewers how they found out about the play, what aspects of regional culture it effectively interpreted, and what they understood to be the central message or lessons in Rambao. Santander Guerrero, a twenty-one year-old local who saw the performance in Lorica, said the play resonated because its title and central character’s name was “a very popular term with us. ‘Rambao’ is a word that we use as… our very own.” At the same time, Guerrero noted that depending on the context, “Rambao” could also function as a slur, indicative of some “defect.”[13] On further reflection, Guerrero said the play was “a work that reflects… the traditions, the ideology of us sinuanos.”[14]

Feedback from audience members and participants in each region demonstrates that the play was wildly popular and generally appreciated. “It is a very cultural work and it brings a message to the people,” Luis Francisco Díaz commented after attending. “It is a work characterized by a few things that are typical… because here it focuses on the problems of a people, the problems that a man has just to be able to subsist, his memories, his cleverness, and all his understandings…” Naturally, not all impressions were positive or enthusiastic. Artist Misael Díaz tells Roger Serpa, after seeing the play in Montería, Cordoba, that, “it doesn’t seem to us that this Teatro Identificador is focusing on the indigenous culture, because the indigenous culture is still much more complex to analyze and is much deeper, and there’s been little research in that sense, right?” Díaz suggested the dances and other aspects of play reflected forms imposed by Spanish conquerors. An ally organization in the broader Negritud movement—the Cimarron movement—critiqued the play along the same lines, issuing a public denunciation of the performance they saw as a commercialization and bastardization of Afro-Colombian culture.[15] Regional popular culture was indeed influenced by Spanish oral traditions, interacting with Afro-Colombian and indigenous cultures to generate what Zapata Olivella and contemporaries called “tri-ethnic” culture. The intent was not to reach authenticity through the identification of some purer indigenous cultural expression, but instead to celebrate—in ways that temporarily turned the tables on the entrenched social order—black, indigenous, and peasant cultures and consciousness as truly representative of Colombia.[16] Still, other interviewees read the performance in urgent, if utopian, ways, as social commentary on the nation’s direction. Carlos Pacheco Mora told Raul Clavijo in Lorica that the message of the play was “primarily the unity of the popular class, for a better future.”

The philosophy behind the Teatro Anónimo Identificador was that these varied expressions of popular culture best approximated an authentic national culture. This experimental theater led by Manuel and Delia Zapata Olivella both built upon and challenged many of the deepest traditions in Latin American theater. Other groups like the Teatro Taller de Colombia[17] helped lead a revival of street theater in Colombia—now with a highly collective and participatory ethos—that connected to a broader movement across the Americas. The Brazilian playwright Boal, a contemporary of Zapata Olivella, dubbed the paradigm “theater of the oppressed” (teatro del oprimido).[18] Mary Roldán views rural theater, radio, and print in the 1960s and 1970s in Colombia as crucial elements of social movements occurring within the post-Vatican II climate.[19] These forms of popular street theater also intersected with the popular education movement in Americas since the 1960s – given a major push forward by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire and others – that included the use of street theater productions as tool for community organizing, popular education, public protest, and cultural expression and preservation.[20]

[1] On Latin American theater see Diana Taylor and Sarah J. Townsend, eds., Stages of Conflict: a Critical Anthology of Latin American Theater and Performance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008); and Diana Taylor, Theatre of Crisis: Drama and Politics in Latin America (Lexington: Univ. Press of Kentucky, 1991). On theater in Colombia see Fernando González Cajiao, Historia del teatro en Colombia (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Cultura, 1986); Gonzalo Arcila, Nuevo teatro en Colombia: actividad creadora, política cultural (Bogotá: Ediciones CEIS, 1983); María Mercedes Jaramillo, El nuevo teatro colombiano: arte y política (Medellín: Editorial Univ. de Antioquia, 1992); and Fernando González Cajiao, ed., Teatro colombiano contemporáneo: antología (Madrid: Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario, 1992), which includes Manuel Zapata Olivella’s “Los pasos del indio.”

[2] Nina S. de Friedemann, "Estudios de negros en la antropología colombiana," in Un siglo de investigación social: Antropología en Colombia, ed. Jaime Arocha and Nina S. de Friedemann, 507-62 (Bogotá: Etno, 1984); “Negros en Colombia: identidad e invisibilidad,” América Negra 3 (1993): 25-38; Peter Wade, “The Cultural Politics of Blackness in Colombia,” American Ethnologist 22, no. 2 (1995): 341-57; and Jaime Arocha and Nina de Friedemann, “Marco de referencia hist6rica-cultural para la ley sobre los derechos étnicos de la comunidades negras en Colombia,” America Negra 5 (1993): 155-72.

[3] Fernando González Cajiao, “Experimento teatral en Colombia: El Teatro Identificador,” Latin American Theatre Review (Fall 1975), 63.

[4] Fernando González Cajiao, ed., Teatro popular y callejero colombiano (Bogotá: Cooperativa Editorial Magisterio, 1997).

[5] Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, Vanderbilt University Special Collections, Grupo etnográfico, Audio cassette, 75-70-C, which includes a recording of most of this performance.

[6] Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, Vanderbilt University Special Collections, Grupo etnográfico, Audio cassette, 75-71-C, which includes a recording of this entire performance.

[7] See the Fundación produced video of the Bogotá show, available on YouTube, credited to manuelzapataolivella.org. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4hRV2q2Xdo.

[8] For a conversation with some of the actors and participants, from March 23, 1975, see Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, Vanderbilt University Special Collections, Grupo etnográfico, 75-75-C.

[9] González Cajiao, “Experimento teatral en Colombia: El Teatro Identificador,” 64.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid, 66.

[12] Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, Vanderbilt University Special Collections, Grupo etnográfico, 75-79-C. This interview includes a team discussion of the survey and evaluation methodology.

[13] The word’s meaning is discussed with several interviewees, including some in Bogotá, in Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, Vanderbilt University Special Collections, Grupo etnográfico, 75-82-C.

[14] Sinuanos are residents of the Sinu River regions of Colombia.

[15] Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, Vanderbilt University Special Collections….

[16] Manuel Zapata Olivella discussed the theater project in Arauca in July 1975. See Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, Vanderbilt University Special Collections, Grupo etnográfico, 75-90-C.

[17] Fernando González Cajiao, “El Teatro Taller de Colombia: La resurrección del atavismo,” Latin American Theatre Review 25, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 73-76.

[18] Julian Boal, “Por una historia política del teatro del oprimido,” Literatura: teoría, historia, crítica 16, no. 1 (June 2014): 41-79.

[19] Mary Roldán, “Acción Cultural Popular, Responsible Procreation, and the Roots of Social Activism in Rural Colombia,” Latin American Research Review 49, Special Issue (2014): 27-44.

[20] Paulo Freire’s extension work in Brazil paralled Zapata Olivella’s with rural communities in Colombia.