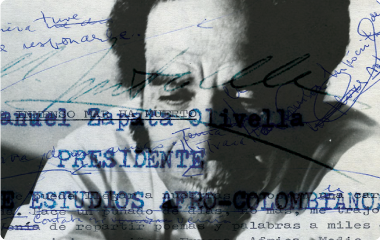

Afro-Colombian intellectual Manuel Zapata Olivella (1920-2004) is known throughout Latin America as the “Dean of Black Literature” and is considered one of the twentieth century’s most important Afro-Hispanic novelists. He was also a noted Colombian anthropologist, folklorist, physician, playwright and screenwriter; his work to document and preserve the history and culture of Afro-Colombia through oral history, television, radio, and literature is legendary.

Zapata Olivella was born in Lorica, in the municipality of Córdoba, in northern Colombia, on March 17, 1920. He spent his early childhood in this rural town before moving to Cartagena with his family in 1927, where he attended school through his first year of medical preparation. During those formative years, Zapata Olivella developed many of the interests that shaped his intellectual inquiries. Thanks to a richly diverse family background, he became deeply committed to the study and promotion of Afro-Hispanic culture in the Americas. His parents, Antonio María Zapata and Edelmira Olivella, were, respectively, a mulato (of European and African descent) and a mestiza (of Zenúe Indian and Spanish descent) who managed to instill in their children a sense of pride and commitment to the tri-ethnic population of Colombia; Zapata Olivella and his six brothers and sisters all became important public figures in Colombia’s academic and artistic circles.

Education was a strong value in the Zapata Olivella household. In fact, the family moved to Cartagena so that Antonio María could attend the Universidad de Cartagena; he was the first black Colombian to graduate from the institution. 1 Accordingly, Manuel Zapata Olivella moved to the capital in 1939 to pursue medical studies at the Universidad de Bogotá. He graduated in 1949, having taken a leave of absence between 1943 and 1944 to travel abroad. During the hiatus between his first and second periods of medical school, Zapata Olivella traveled extensively throughout Latin America, the United States, and Europe. During these explorations, he developed an anthropological eye and became aware of issues that would later provide material for many of his works. Traveling in the United States in 1946 was a particularly relevant influence; because he witnessed racial segregation and discrimination, Zapata Olivella became even more interested in the study of race relations in the Americas.2

In the 1940s, Zapata Olivella, with other Afro-Colombian students, formed the Club Negro de Colombia, an association that organized the first “Día del Negro.” 3 On that celebratory day, students marched on one of Bogotá’s most important avenues to demand the incorporation of African contributions to the nation in Colombian textbooks. The group also expressed solidarity with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, as well as their hopes for a decolonized Africa in the future. Though the Club Negro disappeared quickly, it returned in the 1970s with a different name, Centro de Estudios Afro-Colombianos. Inspired by this institution, Peruvian student José Campos organized and promoted the first Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas, which took place in Cali, Colombia, in 1977. Zapata Olivella served as the Congress’s Secretary General, and later became its President and chief organizer.

As his career both as a novelist and an intellectual flourished, Zapata Olivella began receiving invitations to publish in journals, to give talks and lectures, and to attend and speak at conferences. Several of his novels were translated into English, French, and Portuguese. He also started a fruitful dialogue with intellectuals beyond Colombia, amplifying his network and learning from other scholars who shared some of his interests.

By this time, Manuel Zapata Olivella was publishing extensively and becoming widely known. Between the 1940s and 1990s, his most prolific period as a novelist, he published more than a dozen published novels as well as numerous essays and short stories.4 His works include Tierra mojada (1947), Pasión vagabunda (1948), He visto la noche (1953), China 6 A.M. (1954), La Calle 10 (1960), Cuentos de muerte y libertad (1961), Chambacú, corral de negros (1963), Detrás del rostro (1963), En Chimá nace un santo (1964), El hombre colombiano (1974), El fusilamiento del diablo (1986), Nuestra voz: Aportes del habla popular latinoamericana al idioma español (1987), Las claves mágicas de América (1989), ¡Levántate, mulato! (1990), Fábulas de Tamalameque (1992), Hemingway, cazador de la muerte (1993), La rebelión de los genes (1997), and Nereo: La cámara transhumante (1998). Three of Zapata Olivella’s novels have been published in English: Chambacú: Black Slum (1989), Changó, The Biggest Baddass (2010), both translated by Jonathan Tittler, and A Saint is Born in Chimá (1991) translated by Thomas E. Kooreman.

Zapata Olivella won several prizes for his works, both in Colombia and abroad, including the Premio Espiral (Spain) in 1954, for his dramatic work Hotel de vagabundos. Detrás del rostro was the recipient of the Prêmio Literário Esso in 1962, and then, in 1963, the same novel won the Premio Nacional de Literatura (Colombia). Also in 1963, Corral de negros received an honorary mention from the prestigious Casa de las Américas (Cuba).5 His accolades continued with his masterpiece, Changó, el gran putas (1983) which won the Latin American fiction prize, the Prêmio Literário Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho (Brazil), in 1985. ¡Levántate mulato! (1990), originally published in French in 1987, won the Premio de Derechos Humanos (Paris) in 1988. The following year, Zapata Olivella was awarded the Premio Simón Bolívar (Colombia) for his radio broadcasts on Colombian identity, and in 1995 France named him Chevalier de L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres(Gentleman of the Order of Arts and Letters).

Despite this recognition, Zapata Olivella’s writing never reached the kind of international audience to which he aspired during his lifetime. His final novel, Hemingway, cazador de la muerte (1993) was a personal disappointment in terms of its failure to create the kind of literary recognition he sought outside of Colombia. William Luis recounts that Zapata Olivella “felt that Hemingway’s presence would be of interest to a wider audience, especially one residing in the United States.” 6 Nevertheless, more of his works have been translated in recent years and he has received greater critical attention among Afro-Hispanic scholars7. Since his death in 2004, Zapata Olivella’s works have begun to find its rightful place among Latin America’s most significant writers.

1 Antonio D. Tillis, Manuel Zapata Olivella and the “Darkening” of Latin American Literature. (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2005), 5.

2 Antonio Olliz Boyd, “Manuel Zapata Olivella (17 March 1920-).” Modern Latin-American Fiction Writers: First Series. Dictionary of Literary Biography, 145. (Detroit: Gale, 1992), 315.

3 Laurence Prescott and Antonio D Tillis, “Manuel Zapata Olivella: Introduction,” Afro-Hispanic Review, 25, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 11.

4 Antonio D. Tillis, Manuel Zapata Olivella and the “Darkening” of Latin American Literature. (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2005), 6.

5 Corral de negros was first published in Havana, Cuba by Casa de las Américas in 1963. The novel was republished as Chambacú, corral de los negros by Bedout (Medellín) in 1967 and later translated as Chambacú, Black Slum by the Latin American Literary Review in 1989.

6 William Luis, “Editor’s Note.” Afro-Hispanic Review 25, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 6. Hemingway was published in Bogotá by Arango Editores.

7 See, for example, Jonathan Tittler’s translation of Changó, el gran putas: Manuel Zapata Olivella, Changó, el gran putas, trans. Jonathan Tittler (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2010).