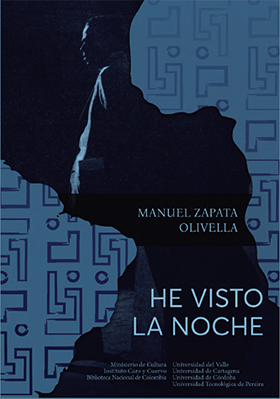

Manuel Zapata Olivella’s He visto la noche (1962) 1 is an often-overlooked literary installment amongst many of his most notable works, such as Changó, el gran putas (1983). 2 He visto la noche contains experiences he had during the end of a four-year period in which Zapata Olivella had abandoned his medical practice in the pursuit of vagabundaje. 3 Initially published in the U.S. in 1953 and then in Cuba in 1962, the book contains forty-eight asynchronous anecdotes in which Zapata Olivella paints a colorful, heart-wrenching image of Black life that he experienced while traveling in the United States. He visto la noche maintains a particular focus on Black folklore, traditions, and hardships within the United States. He discusses the ways in which the lives of Black Americans were impacted by segregation and racism in the United States often focused on the rejection and humiliation black people faced in different parts of the world (e.g., Pasión vagabunda)4 He visto la noche specifically centered around his personal experiences in the United States, the last stop on his long pilgrimage. Zapata Olivella crossed the border from Mexico to the United States in 1946; the discriminatory experiences and trials that followed are what anachronistically comprised his short story, He visto la noche.

Jim Crow Laws in the United States

Despite the ratification of the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery in the United States, Jim Crow Laws5 propagating the poisonous mantra “separate but equal”6continued to pervade and infect the United States in the mid-1950s. In an He visto la noche chapter titled “Jim Crow en Hollywood,” Zapata Olivella wrote of his personal experiences with racism while in Los Angeles attempting to sell his script, El Rey de los cimarrones, to Hollywood producers. “Me quedé boquiabierto ante aquella revelación que echaba por tierra las ilusiones en que fundamentaba el éxito de mi obra: la figura descollante, brava y heroica de un africano luchando por su libertad. Hasta había pensado que Paul Robeson habría podido ser su protagonista” . The effect of Jim Crow on racial inequality made his script unsalable in Hollywood. His script revolved around an African man fighting for his freedom, requiring a black lead actor which Hollywood was adamantly against casting. Later in his career Zapata Olivella successfully sought out less discriminatory publishing and film companies.

Friendship with Langston Hughes

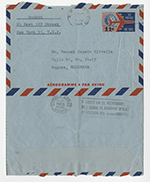

James Mercer Langston Hughes was a notable American writer, poet, activist, playwright, and leader of the Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s whose career spanned the ‘20s through the ’60s. His friendship with Manuel Zapata Olivella extended over two decades. They met in 1946, three years into Zapata Olivella’s travels beyond Colombia while in New York City. In a chapter titled “Resurrección,” Zapata Olivella describes their encounter in which, desperate and hungry, he sought out Langston Hughes, a fellow writer whom he had admired. In Hughes, he found more than a fellow writer of Black literature: Hughes also proved to be a kindred spirit and longstanding good friend. Beyond their shared passion for writing, both had experienced “pasión vagabunda.”8

Langston Hughes contributed to Zapata Olivella’s growth as a writer while Zapata Olivella gave Hughes a deeper perspective on the Black experience in Latin America. He also contributed to Zapata Olivella’s understanding of the African American struggle for racial equality in the United States. Beyond the impact each had in understanding racial themes in the US and globally, Hughes informed him by letter that he had sent Zapata Olivella’s play, Mangalonga, El Liberto, to the director of Circle in the Square in New York City. Hughes incorporated Zapata Olivella into his sphere as a prominent intellectual and writer in New York City9 , inviting him to plays and social gatherings.

El Ángel de los vagabundos

Manuel Zapata Olivella combined both his personal experiences and his observations of African American life to synthesize a narrative in which he crafted a colorful tapestry of the experiences of American society and discrimination in He visto la noche. Eager to discover the world beyond his homeland and touched by a passion for wandering, Zapata Olivella embarked on a journey which took him to several regions of Central and South America before traveling to Mexico, where he then crossed the Mexican border into the United States. The weight of his experiences as a wandering traveler is further impressed upon us by the knowledge that he had abandoned his medical practice and all that he knew domestically in pursuit of his passion for writing. Throughout his narrative his despondent observations are punctuated by fleeting, glowing moments of hope. He depicts great women, such as his Chicagoan friend, Paulina, who helped him find work in a hospital when he had no other options, and men such as his good friend and fellow writer Langston Hughes. Upon his arrival in the United States with only his typewriter, Zapata Olivella did not find an easy life awaiting him. In He visto la noche he wrote of having little money and no pre-established connections to help garner a position as a journalist or screenplay writer in America. Although Zapata Olivella faced many hardships, such as homelessness and hunger, he overcame his struggles with the assistance of those he called “Angels,” who came to him in the form of kind strangers offering their homes, food, and a job. Hope is enshrined in what Zapata Olivella describes as “el ángel de los vagabundos:”10 those he encountered along his journey, such as Jorge who let him live in his apartment when he had nowhere else to go, and Paulina who helped him find a hospital job when his script did not sell. He visto la noche depicts themes of wandering adventure, racial inequality, and the spirit of compassion. Zapata Olivella’s experiences while traveling influenced his later activism and his conferences and congresses on civil rights and the equality of races.

Bibliography

Orozco, Wilson (2012). He visto la noche de Manuel Zapata Olivella: El viaje de un marginal en la búsqueda de sus raíces/He visto la noche by Manuel Zapata Olivella: The trip of a marginal person in search of his roots. Estudios de literatura colombiana, (31), 267-273. http://proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?&url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1431279369?pq-origsite=primo

Prescott, Laurence E. (n.d.). “We, Too, Sing America:” The Asociación de Colombianistas. https://colombianistas.org/wp-content/themes/pleasant/biblioteca%20colombianista/03%20ponencias/14/prescott_ponencia.pdf

Prescott, L. E. (2006). “Brother to Brother: The Friendship and Literary Correspondence of Manuel Zapata Olivella and Langston Hughes.” Afro-Hispanic Review, 25(1), 87–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23054705

Prescott, L. E., and Antonio D. Tillis (2006). INTRODUCTION: Manuel Zapata Olivella. Afro- Hispanic Review, 25(1), 9–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23054699

Prescott, L. E. (2001). “Afro-Norteamérica en los escritos de viaje de Manuel Zapata Olivella: Hacia los orígenes de “He visto la noche.” Afro-Hispanic Review, 20(1), 55–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23054510

Prescott, L. E., and Antonio D. Tillis, (2006). Manuel Zapata Olivella. Afro-Hispanic Review, 25(1), 9-14,252-253. Retrieved from http://proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/manuel-zapata-olivella/docview/210673630/se-2?accountid=14816

Zapata Olivella, Manuel (1962). He Visto la Noche. Biblioteca del pueblo. San Rafael, Impr. Nacional de Cuba.

1 Manuel Zapata Olivella, He visto la noche (San Rafael: Impr. Nacional de Cuba, 1962).

2Manuel Zapata Olivella, Changó, el gran putas (Bogotá: Editorial Oveja Negra, 1983).

3 Vagabondage

4 Manuel Zapata Olivella, Pasión vagabunda: (Relatos) (Bogotá: Editorial Santafé, 1949).

5 Jim Crow law refers to any of the U.S. laws that enforced racial segregation between the late 1800s and mid-1950s

6 A U.S. legal doctrine which stated racial segregation did not violate the U.S. Constitution.

7 Zapata Olivella, 1962, 75.

8 Wandering passion

9 Langston Hughes to Zapata Olivella, July 1, 1963.

10 Angel of the vagabonds.