In 1943, after finishing his fifth year in medicine, at the Universidad Nacional de Bogotá, Manuel Zapata Olivella traveled to México City? where he stayed for two years. During his trip, Zapata Olivella met the muralist artists José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, and other writers and intellectuals such as José Vasconcelos, Mariano Azuela, Alfonso Ortiz Tirado, Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, José Revueltas, Agustín Yánez, and Ciro Alegría. 1

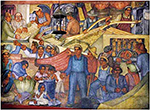

Thanks to Luis Moya, a Mexican designer, Zapata Olivella met the doctor, composer, and singer Alfonso Ortiz Tirado. He greeted him and said: “I am a Colombian, a last-year medical student, and I am hungry.” Ortiz Tirado hugged Manuel and called him, “Son.” 2 From that time on, Tirado not only gave him work, but also his unconditional friendship. While working at Ortiz Tirado’s Clinic, he met the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, who was suffering from pneumonia. In gratitude for Zapata Olivella’s dedication, Rivera asked what he could do to thank him, and Zapata Olivella suggested that Rivera use his facial features for one of his characters in the murals in the Palacio de la Secretaría de Educación. Rivera captured his likeness in one of the faces of the indigenous workers.

Zapata Olivella held all kinds of jobs during his time in Mexico: “I was forced to work in all types of occupations: as a pugilist, a wrapper, a stevedore, and many other jobs, not pleasant at all.” 3 He also began what was to become a long-term collaboration with several Mexican magazines and journals. Martín Luis Guzmán, author of Entre el águila y la serpiente (1928), made him the editor-in-chief of the section “Latinoamérica” (Tiempo magazine), where he worked for more than a year. He reviewed films and performances for Revista Panorama and he was the editor of the section “Psicoanálisis individual” in the magazine, Sucesos para todos.

Zapata Olivella also reported on Mexican life for the weekly newspaper Hoy, owned, and operated by Regino Hernández Llergo.4 He continued in this role as a correspondent while in the United States, where he wrote a series of articles in which he denounced the racial discrimination of Afro-Americans and Latinos in the United States, later collected in the volume, He visto la noche (1953).

México’s Influence in his Later Fieldwork: A Zambo Writer, Folklorist, and Anthropologist

The representation of Zapata Olivella as an indigenous person in the mural by Rivera could be considered a mere coincidence, but in fact it is an appropriate metaphor to illustrate his ideas surrounding race in the Americas. He sees the Indian and the Afro-descendant as related entities:

the blacks in the Americas are the result of miscegenation. The first and most essential of all those mixes is our condition as Afro-Americans. Then, there is the muddled mix of blood with white, mulatto and with the Indian. The richness of blackness spread through the kitchens, the patios, hallways, and the bedrooms of the masters: zambaigo, lobo, cambuyo, chamiso, caboclo, cafuso, torna-atrás.5

Zapata Olivella saw himself as a zambo—a mix of Indian and African—not only in a physical sense, but also philosophically and religiously: “mythology is some concrete, daily, nurturing reality. The dead and the living are existent beings, united by a pact of mutual alliance” 6; “In my home I learned Catholicism from my mother and the philosophy of free thought from my father.”7 His later fieldwork photographs illustrate his interest in showcasing the transculturation—as depicted by Fernando Ortiz8 — of Catholic and non-Catholic religious practices.

His experiences in Mexico are essential to understanding his ideas about race. He was highly influenced by José Vasconcelos’ writings on the “cosmic race.” Zapata Olivella saw him as a visionary but opposed the segregation of the Aztec, Mayan, and Olmec cultures posited by Vasconcelos, who viewed those indigenous cultures as barbaric. Vasconcelos believed that these barbaric peoples would be civilized and enriched through the miscegenation of European civilization in the Americas. According to Zapata Olivella, Vasconcelos ignored the origins of European culture and civilization and the fact that Spain had been nourished by Mesopotamia and fed on Egyptian culture.9

Some of Zapata Olivella’s principal concepts, such as “el autorracismo” (self-racism), refutes Vasconcelo’s works: “Colombian people do not accept or take pride in the ethnic groups they have. They try not to be Indians, when there is an indigenous heritage; Colombians do not want to be African, even though they cannot deny it because of the color of their skin, flat nose, and thick lips. If they claim to be pure white, they are so racist that they do not want to be even of Spanish descent, but of German or English.”10

México in Zapata Olivella’s Writings: The Novel Changó, el Gran Putas

His first sojourn to Mexico would later appear in his literary works, especially in Pasión vagabunda and He visto la noche, but the most representative reformulation of the ideas he acquired during his stay in Mexico appear in Changó el gran putas (1983), an epic text whose development took him more than twenty years to write.

Zapata Olivella uses the historic figure of José María Morelos as a character for his chapter, “El llamado de los ancestros.” Morelos, a mestizo depicted by Rivera in his murals, was a Mexican priest and a 19th-century leader of the war for independence. According to Zapata Olivella, the Olmec civilization of Mexico was “the placenta of the European culture:” “It is the zamba dimension of the black in Mexico.” In describing Changó, el gran putas, he writes: “I start from the Olmec ancestors [ “powerful ngangas”], the first Africans in this continent, to culminate with the revolt of the priest Morelos against the slavery of Indians and blacks.” 11

“El llamado de los ancestros” opens with the apparition to José María of the Virgin Mary, depicted as a black woman: Ngafúa, messenger of Changó. José María is recreated as the Chosen One to “restore the dignity of the Indians, and oppressed blacks their mestizo, zambos, and mulatto descendants.” 12 Zapata Olivella describes the last moment of José María’s imprisonment and death: the character is portrayed as an Afro-descendant, “his long beard made him more African and fearsome.”13 José María is —in aspect and ideology— the zamba dimension of the black in Mexico.

Mexico was the location in which he developed his notion of miscegenation. This concept also permeates his notion of “el putas,” essential in the configuration of Changó

In the socio-historical field, it can be said that el Putas also represents the supernatural forces, generally protective, derived of the indigenous naturalistic cults (sun, moon, lagoon), and of the different myths and traditions of the African culture…. This traditional, popular culture is simple and is the sum of the knowledge of our mestizo people…. If we look a little at the Colombian oral tradition, we find the idea of a devil, projecting himself on himself, from his existence and wisdom, it is as remote as the moment in which our multi-ethnic culture is integrated: Indigenous, European, and African.14

México was essential to his understanding of his own culture and the starting point for developing a “sociology of ethnicity” —in the words of William Mina Aragón. Zapata Olivella wrote in newspaper piece:

From 1943 to 1947, I had the opportunity to spiritually nourish myself with a series of concepts about Mexican culture and I think that from that moment, I reinforced that childhood concern for the knowledge of my own culture, but already with a much broader vision. I believe that this is one of the most important sources in the spiritual formation of the conception of culture within literature. 15

His fieldwork, his radio programs, and his literary and scholarly works highlight the mulatto, zambo, and mestizo peoples who have survived four centuries of colonial exploitation through their creativity, mythology, songs, philosophy, and their growing rebellion. Zapata Olivella’s conception of the miscegenated Latin American subject became a way of developing cultural “rhizomes” that connect and nourish the whole Latin American space, despite its long history of colonial social relations, whitening processes, racial misconceptions, and prejudices.

Bibliography

Sierra García, Antonio. “Toda gente: Configuration of Hoy Magazine”, Interpretextos, U de Colima 10 (2013): 53-72. http://ww.ucol.mx/interpretextos/pdfs/382_inpret1008.pdf

Harris, Mardella and Manuel Zapata Olivella, “Entrevista con Manuel Zapata Olivella.” Afro-Hispanic Review 10, no. 3 (1991): 59-61.

Hernández Cuevas, Marco Polo. “La Virgen Morena mexicana: Un símbolo nacional y sus raíces africanas.” Afro-Hispanic Review 22, no. 2 (2003): 54-63.

Mina Aragón, William. “Zapata Olivella: Escritor y humanista.” Afro-Hispanic Review, 25, no. 1 (2006): 25-38.

Montiel, Meryt C. “Defensor del mestizaje.” El País (1995). Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Pera Chalá-Grandin, Lucía. “Manuel Zapata Olivella, « El Ekobio Mayor » 1920-2004.” Présence Africaine, Nouvelle série, No. 172 (2005): 175-79.

Ratcliff, Anthony “‘Black Writers of the World, Unite!’ Negotiating Pan-African Politics of Cultural Struggle in Afro-Latin America.” The Black Scholar, vol. 37, no. 4, (2008): 27-38.

Riaño, Anita. “Sigo al personaje más allá de su vida a la luz del sol”. El tiempo (n. y.) Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Zapata Pérez, Edelma. “Manuel Zapata Olivella: La visión cósmica en mis huellas ancestrales.” Afro-Hispanic Review, vol. 25, no. 1 (2006): 15-23.

Zapata Olivella, Manuel and Margarita Krakusin. “Conversación informal con Manuel Zapata Olivella.” 2000 (unpublished). Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Interviews,” BOX 4, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

—— et al. “El diablo no es tan malo como lo pintan.” El Espacio, vol. 25, no. 7 (1989) Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

—— et al. “Manuel Zapata Olivella: La voz de la identidad cultural latinoamericana.” Pijao: Arte y Literatura Latinoamericana. no. 5 (1990-1991). Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Interviews,” BOX 4, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

——. “El novelista cuenta su experiencia al más allá de la vida y la muerte.” (Unpublished interview), “Interviews,” BOX 4, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

——. Changó el gran putas. Bogotá: Ministerio de Cultura de Colombia, 2010.

——. He visto la noche. Bogotá: Editorial Los Andes, 1953.

——. Pasión vagabunda: (Relatos). Bogotá: Ministerio de Cultura, Instituto Caro y Cuervo y Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, 2000.

——. Tierra mojada. Bogotá: Espiral, 1947.

1 Alegría’s preface to Zapata Olivella’s Tierra mojada in 1947.

2 Manuel Zapata Olivella, “El novelista cuenta su experiencia al más allá de la vida y la muerte,” (Unpublished interview), “Interviews,” BOX 4, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN: 4

3 Anita Riaño and Manuel Zapata Olivella, “Sigo al personaje más allá de su vida a la luz del sol,” El Tiempo(n. y.) Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN: 5

4 For more information about Hoy and the intellectuals nucleated around this weekly magazine, see Antonio Sierra García’s “Toda gente: Configuration of Hoy Magazine”, U de Colima, 53-72. http://ww.ucol.mx/interpretextos/pdfs/382_inpret1008.pdf

5 Manuel Zapata Olivella, “El novelista cuenta su experiencia al más allá de la vida y la muerte,” (Unpublished interview), “Interviews,” BOX 4, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN: 4

6Ídem.

7 Meryt C. Montiel, “Defensor del mestizaje,” El País (1995). Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

8 “Transculturation” is a term coined by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz to describe the phenomenon of merging and converging cultures.

9 Margarita Krakusin and Manuel Zapata Olivella, “Conversación informal con Manuel Zapata Olivella,” 2000 (unpublished). Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Interviews,” BOX 4, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

10 Meryt C. Montiel, “Defensor del mestizaje,” El País (1995). Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

11 Manuel Zapata Olivella, “El novelista cuenta su experiencia al más allá de la vida y la muerte,” (Unpublished interview), “Interviews,” BOX 4, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN: 5

12 Manuel Zapata Olivella, Changó el gran putas. (Bogotá: Ministerio de Cultura de Colombia, 2010) 409.

13 Ídem, 410.

14 Manuel Zapata Olivella, et al., “El diablo no es tan malo como lo pintan,” El Espacio, vol. 25, no. 7 (1989) Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

15 Meryt C. Montiel, “Defensor del mestizaje,” El País (1995). Manuel Zapata Olivella Papers, “Newspapers Clippings,” BOX 8, Special Collections Library, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.