Spanning more than fifty years, Manuel Zapata Olivella’s career as a prominent Colombian intellectual is highlighted by his correspondence with many colleagues and collaborators. As a prominent member of Colombia’s literary circles and an ardent promoter of the cultural contributions of Afro-Colombians, Zapata Olivella led an active and productive intellectual life. His ongoing correspondence with U.S. intellectuals including ethnomusicologist George List, literary scholars Laurence Prescott, Marvin A. Lewis, Yvonne Captain-Hidalgo, William Luis, Antonio D. Tillis, and Jonathan Tittler, among others, shed light on the scope of his work and interests. Zapata Olivella was a generous and eager colleague, as well as a savvy promoter of his own writing and research interests. Of course, his work required the development and maintenance of relationships of mutual benefit as well as the development of useful connections that facilitated invitations to lectures abroad.

George List

Along with his numerous contacts in literary circles, Manuel Zapata Olivella worked closely with ethnographers and anthropologists interested in preserving the legacies of Colombia’s rural populations. One such collaboration was Zapata Olivella’s work with noted Indiana University ethnomusicologist George List (1911-2008). List and Zapata Olivella corresponded regularly, and Zapata Olivella was an invaluable resource for List because of his knowledge of Colombian regional dialects, specifically “costeño,” an Afro-Colombian coastal dialect. In a letter dated November 11, 1993, Zapata Olivella painstakingly defines fifteen words in response to List’s request. Zapata Olivella notes that he has responded “con mucho cuidado he respondido a tus preguntas, teniendo a la mano un diccionario de regionalismos costeños, rememorando el habla de los campesinos y consultando con paisanos de la región. Así, pues, puedes dar bastante confiabilidad a las respuestas” [“I have responded to your questions with great care, having on hand a dictionary of coastal regional speech, recalling how peasants speak and consulting with people of the region. So, then, you can be quite confident in my answers”]. List was grateful for Zapata Olivella’s help, and invited him to Indiana University and to write an introduction to his work as well as to collaborate with other colleagues on their projects. In a January 7, 1992 letter to List, Zapata Olivella refers to the introduction he wrote for the Spanish translation of List’s latest book Música y poesía en un pueblo colombiano: una herencia tri-cultural (1994), originally titled Music and Poetry in a Colombian Village (1983). In this letter, Zapata Olivella also mentions his novel Hemingway, cazador de la muerte (1993) and his hope for its forthcoming publication. List’s groundbreaking contributions to the field of ethnomusicology and Colombian folklore are due in part to his collaboration with Zapata Olivella.

Laurence E. Prescott

Perhaps Zapata Olivella’s closest friendship and longest lasting collaboration was with Laurence E. Prescott, currently Professor Emeritus of Spanish and African American Studies at Pennsylvania State University. Prescott is a pioneering scholar in the fields of Afro-Latin American literature and culture, Afro-Colombian writers, and African American life and culture in Latin American travel writings. Beginning in the early 1980s, Prescott and Zapata Olivella regularly exchanged letters about their professional projects, families, and successes and failures as scholars. In a letter dated May 27, 1981, Prescott writes to Zapata Olivella from his new post in Bloomington, Indiana about finishing his doctoral thesis as well as his excitement about Zapata Olivella’s “largamente esperada” [“long-awaited”] novel, Changó, el gran putas (1983). Their correspondence would continue until Zapata Olivella’s death in 2004, by which time they had become life-long friends. For example, in a letter dated October July 25, 1996, Prescott includes news about his family, his own forthcoming publications in The Afro-Hispanic Review and an invitation to contribute to a book-length study on Afro-Hispanic literature, and plans for Zapata Olivella’s visit to Washington University in St. Louis. Referring to each other as “ekobios,” a term Zapata Olivella uses to express the notion of a bond of brotherhood based on African origins and shared experience, Zapata Olivella and Prescott organized conferences, read each other’s work, and kept each other abreast of funding opportunities. 1

Yvonne Captain-Hidalgo

Zapata Olivella was not only interested in collaboration with established scholars in the growing field of Afro-Colombian and Afro-Latin American literatures. As a doctoral student at Stanford University, Captain-Hidalgo received an invitation from Zapata Olivella to the Primer Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas in Cali, Colombia on August 28-29, 1977. At the time, Captain-Hidalgo’s dissertation focused on Zapata Olivella, and she was eager to establish ties with the writer who would figure prominently in her academic career. In a letter dated August 5, 1983, Captain-Hidalgo mentions her efforts to publish an interview she conducted with Zapata Olivella in 1980, offers to translate Changó, el gran putas, and proposes that Zapata Olivella visit her department. Five years later, in a letter dated January 27, 1985, Captain-Hidalgo again invites her friend and mentor to give a lecture at her university, while also suggesting possible future collaborations. Currently an associate professor of Latin American Literature and Film and International Affairs at George Washington University’s Department of Romance, German, and Slavic Languages and Literatures, Captain-Hidalgo has risen to prominence in the field of Afro-Hispanic studies.

Jonathan Tittler

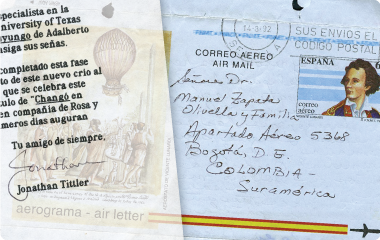

Zapata Olivella’s friendship and correspondence with Jonathan Tittler also began with mutual academic interests. Tittler and Zapata Olivella met in Medellín at the inaugural Association of Colombianists in 1984. At the time, Tittler was the president of the North American Association of Colombianists and was eager to establish ties with Zapata Olivella. After this meeting, the two communicated regularly, first by post, then by fax, and finally, as Tittler explains in his translator’s note to his 2010 English translation of Changó, el gran putas (1983), via email until Zapata Olivella’s death in 2004. 2 Tittler first translated Zapata Olivella’s Chambacú, corral de negros (1967) (Chambacú, Black Slum, 1989) Their working relationship quickly became a lasting friendship as Tittler worked tirelessly to first translate and then publish Zapata Olivella’s Changó in English. In one of their many letters to each other, Tittler mixes news about possible publishers for Changó with news of his own failing health and his regrets about not being able to attend an upcoming Asociación de Colombianistas Conference . As a professor at Cornell University’s Department of Romance Studies and later at Rutgers University’s Camden Campus, Tittler was a valuable resource for Zapata Olivella, not just as a translator, but also for information about programs for visiting scholars, grants, lectures, and conference opportunities.

1 Julia Cuervo Hewitt, Voices Out of Africa in Twentieth-century Spanish Caribbean Literature, (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2009), 255.

2 Jonathan Tittler, “Translator’s Note and acknowledgements,” in Changó, the Biggest Baddass, trans. Jonathan Tittler (Lubbock, TX: University of Texas Press, 2010), ix.