Although African slavery formally ended in the Americas in 1888, when Brazil finally abolished the institution, blacks continued to endure hardships for decades all over the continent. “Freedom” did not always mean equal rights or opportunities, or even political or economic participation. In Colombia, where slavery was pervasive, its effects were long-lasting. In the post-independence period, the “myth of racial harmony” characterized a discourse that was, in theory, inclusive of Afro-Colombians, when in reality this population continued to face exclusion.1 According to Peter Wade, one of the foremost scholars of race in Colombia, unlike the local indigenous population, blacks had no separate juridical identity, which posed an extra challenge to the fulfillment of racial democracy.2 Disregarded by the state, Afro-Colombians also faced the silence of academics: as Nina Friedman points out, throughout the twentieth-century anthropologists were largely concerned with indigenous communities; sociologists focused on peasants and class relations, while historians studied slaves but often disregarded other aspects of black experience.3

Although there were efforts to promote black culture in the 1940s and 1950s, mainly by Manuel Zapata Olivella, it was not until the 1970s that things began to change. Zapata Olivella had founded the Club Negro de Colombia together with other Afro-Colombian students in the 1940s, and while the association organized the first “Día del Negro”, as an institution it was short-lived.4 Three decades later, a larger group of black artists and intellectuals who had had access to higher education arose; they created cultural groups and started articulating for change.5 They were inspired by the black activism they had grown up watching succeed in other places in the 1950s and 1960s, such as the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power and Black Art movements in the United States, the anti-Apartheid struggles in South Africa, and the fights for independence in Angola, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, and Mozambique of the 1970s. The latter also inspired black activism in Brazil, where the military dictatorship had been supporting Portugal against independence advocates in Africa, hence providing a South American counterpart for Afro-Colombians. The Club Negro de Colombia reappeared in the 1970s under the name Centro de Estudios Afro-Colombianos, and several other groups were also formed to advocate for black’s inclusion in Colombia’s national discourse. In addition to the Centro de Estudios Afro-Colombianos, Manuel Zapata Olivella also founded the Fundación Colombiana de Investigaciones Folclóricas, and his sister, folklorist and dancer Delia Zapata Olivella, created the Fundación Palenque. In 1975, sociologist and journalist Amir Smith-Córdoba founded the Centro para la Investigación y el Desarrollo de la Cultura Negra, which published the journal Presencia Negra. In 1976, another prominent Afro-Colombian intellectual, Juan de Dios Mosquera, founded the Círculo de Estudios de la Problemática de las Comunidades Afrocolombianas–SOWETO, which would later organize the Movimiento Nacional por los Derechos Humanos de las Comunidades Afrocolombianas (the Afro-Colombian Communities’ Human Rights National Movement), also known as CIMARRON (1982).6

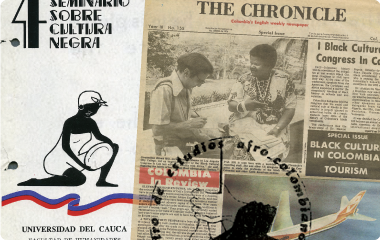

First Congress of Black Culture in the Americas

It was in this context of cultural and political activism that the Primer Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas (First Congress of Black Culture in the Americas) took place, in Cali, Colombia, on August 24-28, 1977, organized and sponsored by the Fundación Colombiana de Investigaciones Folclóricas (Colombian Foundation to Investigate Folklore), the Asociación Cultural de la Juventud Negra Peruana (Cultural Association of Black Peruvian Youth), and the Centro de Estudios Afro-Colombianos (Center of Afro-Colombian Studies). The motivation to plan such an event came from the organizers’ perception of the continued effects of the slave system on the black population in the Americas. On October 12, 1976, they issued a call for the congress, urging the black population of the continent to gather at the First Congress of Black Culture in the Americas to study and discuss sociocultural aspects relating to the African diaspora in the continent, joining forces to affirm black identity throughout the region. “The moment has come to leave lamentations behind and strike out for genuine vindication,” read the English version of the text.7

The Congress was organized by six key objectives: to increase ethnographic, social, economic, psychological, political, and artistic studies that included blacks as part of the historical context; to reassess African values and contributions according to the sentiment and aspirations of the black population; to unite actions and goals of those researching black culture in the continent; to plan future research; to foster the creation of organizations dedicated to the study of African-American values across the region; and to promote the establishment of a fund to foster and develop black culture in the Americas.

The opening plenary took place in the afternoon of August 24, 1977. Delegates elected the Congress’s executive committee, designating Manuel Zapata Olivella as President, Roy Simón Bryce-Laporte (Panama) as secretary, and Eulalia Bernard (Costa Rica), Olivia Sera Avellar (Brazil), and Wände Abimbola (Nigeria) as executive delegates. Participants also established four working groups where they presented their papers: black ethnicity and mestizaje, philosophy and affectivity, social and political creativity, and material and artistic creativity. Each of the working-groups was to meet, discuss, and present suggestions relating to their topic to the general assembly. This body, in turn, was to deliberate on general recommendations to guide the course of studies on black culture in the Americas.8 Participants included scholars, writers, artists, and intellectuals from Angola, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, Egypt, Spain, the United States, Honduras, Mexico, Nigeria, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico, Senegal, as well as members of UNESCO and OAS (Organization of American States). Given the diversity and linguistic complexities of the Black World, Congress proceedings were convened in Spanish, Portuguese, English, and French. Papers could be submitted and presented in any of these four languages, and the organizing institutions made a commitment to translate them into at least one other official language.9

In his inaugural speech, Manuel Zapata Olivella recognized that this was not the first time regional meetings had been convened to investigate black presence in the Americas. He reminded the audience that similar events had happened in the Caribbean and Antilles, as well as in the United States, Spanish America, and Brazil. Nonetheless, he stressed that the Cali gathering was the first to embrace a continental scope. By adopting national or regional frames, previous congresses had not succeeded in encouraging black dialogue and exchange across the Americas—a shortcoming that the Primer Congreso sought to address. Despite language barriers, the main goal of the Cali meeting was to examine the essence of African identity in the continent.10 Zapata Olivella also called attention to the fact that, despite the massive presence of blacks in the region, few schools on the continent offered African history classes. He reminded the audience that blacks were largely prevented from participating in political, economic, cultural, religious and artistic life, and that, when they did, their contributions were often denigrated. In face of such findings, Zapata Olivella proposed that the Congress petition national governments across the Americas for the formal inclusion of studies of black culture into school curricula. He also proposed that regional and international organizations, such as OAS and UNESCO, sponsor future sessions of Congresos de la Cultura Negra de las Américas.11

In its resolutions, this first congress ratified a series of propositions that spoke to its political and Pan-African tone.12 One of the first suggestions participants agreed upon was to issue a “Declaration of Solidarity” with the anti-Apartheid movement and African liberation struggles. They also condemned US imperialism and dictatorships in Latin America, and recognized the double burden of race and gender imposed on black women, hence urging men all over the continent to support women’s liberation.

According to Anthony Ratcliff, even though the First Congress was not a mass social movement, it nonetheless played a central role in fostering a network of blacks on a trans-continental scale. After the 1977 Cali meeting, these linkages would continue to flourish. The first congress, thus, served “as a model for various contemporary Afro-descendant movements in the Americas against racism, sexism, land displacement, and class exploitation.”13 Recognizing the success of the event, activists convened subsequent editions of the Congress.

Second, Third, and Fourth Congresses of Black Culture in the Americas

The second Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas took place in Panama, on March 17 1980, this time hosted by the Centro de Estudios Afro-Panameños (CEDEAP, or Center for Afro-Panamanian Studies). Approximately three hundred people participated, and in addition to countries represented in the previous congress, Caribbean countries such as Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad, Cuba, and Haiti also sent delegates to this meeting. Papers focused on the topics of race and class, formal and informal education, cultural pluralism and national unity, and perspectives for blacks in the Americas. As in the first congress, the second also kept a political tone by expressing solidarity with independence struggles in Puerto Rico, Belize, Martinique, Guadalupe and Cayenne. Final resolutions also condemned racist actions by the Ku-Klux-Klan in the United States and by the death squad in Brazil. Most importantly, participants decided to formally establish the Congress of Black Culture in the Americas as a permanent forum through which to fight racism and discrimination in the Americas and the world.

The third Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas met in São Paulo, Brazil, in August of 1982. The announced theme was "Diáspora africana: conciencia política y cultura africana" (African Diaspora: Political Conscience and African Culture). Two hundred activists attended, among them writers, artists, and scholars. In addition to the continued support for anti-Apartheid efforts in South Africa, the Congress also expressed solidarity with Palestinians and Namibians, and urged labor and peasant unions of the continent to join forces in order to fight racism in the Americas. The concluding plenary session also voted for the creation of an international journal, titled “Afro-diáspora.” It was agreed that the next Congress would take place in Grenada, where black revolutionary Maurice Bishop was in power, but US military intervention in the island in October of 1983 forced organizers to change their plans.

In face of this unexpected turn of events, Manuel Zapata Olivella presented an ambitious idea: that the fourth Congreso be held in 1991, alongside celebrations of the fourth centenary of Columbus’s arrival on the continent. The title would be “Afro-América y la Comunidad Europea en la Perspectiva del Siglo XXI”. He managed to secure financial and logistical support from UNESCO. The fourth congress was to take place in Europe, in an effort to bring more European countries into the conversation about the African Diaspora, as well as to gain world-wide publicity. Zapata Olivella first thought of Badajoz, in Spain, as an ideal site for the meeting, given its privileged location bordering Portugal and considering both Spain and Portugal’s role in the African Diaspora. Later, it was decided that the Congress would happen in Paris, at the international office of UNESCO. Given the size of the event, regional meetings were planned in preparation for the bigger conference. A series of complications, however, forced another change of plans, and the 1991 Paris meeting was postponed. Organizers made an effort to host it in the United States, but those efforts also did not come to fruition. Nonetheless, the four Congresos were extremely significant in the promotion of continental activism and intellectual exchange among the Afro-descendant populations of the Americas.

1 Marixa Lasso, Myths of Harmony: Race and Republicanism in the Age of Revolution, Colombia, 1795-1831 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007).

2 Peter Wade, “Definiendo la negridad en Colombia,” in Estudios afrocolombianos hoy: aportes a un campo interdisciplinario, ed. Eduardo Restrepo (Popayán: Editorial Universidad del Cauca, 2013), 21-37; 22. See also his Blackness and Race Mixture: The Dynamics of Racial Identity in Colombia (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993).

3 Nina Friedman, “Estudios de negros en la antropología colombiana,” in Un siglo de investigación social: antropología en Colombia, eds. Jaime Arocha and Nina Friedman (Bogotá: Etno, 1984), 507-572.

4 Laurence Prescott and Antonio D. Tillis, “Manuel Zapata Olivella: Introduction,” Afro-Hispanic Review 25, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 11.

5 Peter Wade, “The Cultural Politics of Blackness in Colombia,” American Ethnologist, 22:2 (1995): 342-358.

6 Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango del Banco de la República, "El Renacimiento Afrocolombiano." Online publication. <http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/sociologia/estudiosafro/estudiosafro18.htm> Accessed 11/10/2014; Anthony Ratcliff, "‘BLACK WRITERS OF THE WORLD, UNITE!’ Negotiating Pan-African Politics of Cultural Struggle in Afro-Latin America,” The Black Scholar 37, no. 4, (Winter 2008): 27-38; 28.

7 Fundación Colombiana de Investigaciones Folclóricas/UNESCO, “Antecedentes: Circular anunciando la convocatoria del Primer Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas, Bogotá, Octubre 12 de 1976,” in Primer Congreso de la Cultura Negra de las Américas. Cali-Colombia. Homenaje a León Goutran Damas. (Bogotá: Fundación Colombiana de Investigaciones Folclóricas/UNESCO, 1988), 3. The original reads: “Ha llegado el momento de pasar de las lamentaciones a las reivindicaciones concretas.”

8 Ibid., 7. See also Ratcliff, “Black Writers of the World, Unite!,”33.

9 Primer Congreso …, 5-7.

10 Ibid., 19-20.

11 Ibid., 21.

12 Ratcliff, “Black Writers of the World, Unite!,”34.

13 Ibid.,27.

14 Segundo Congreso de Cultura Negra de las Américas: tema, identidad cultural del negro en América: informe de comisiones y resoluciones, Panamá́, 17-21 marzo, 1980. (S.l.: s.n., 1980); Eduardo Tamayo, “Abriendo el camino: Congresos de la cultura negra de las Américas.” Online publication. http://alainet.org/active/999&lang=es Accessed 12/05/2014.