Discussions about national identity in Latin America date back to the independence period, when local elites struggled to define the character of the new republics emerging from the Iberian Empires.1 Due to the high levels of miscegenation of colonial societies, race was central to the debates dealing with national identity. What would be the role of people of mixed descent in the new republican order? Were slaves and indigenous populations to be incorporated as citizens? Who could vote, and who was eligible to run for office? These were some of the questions at play during the Spanish American Revolutionary era and the independence era that followed.

Colombia was no exception. It had the third largest population of Africans and those of African descent in the Americas, after Brazil and the United States (and the first in Spanish America).2 Cartagena, on the Caribbean coast, was a principal slave trade port in the Atlantic; thousands of Africans disembarked and were sent as slaves to other parts of the Viceroyalty, especially to the mining areas in the West.3 But these people were denied most privileges, as a system of racial hierarchy barred slaves and even free people of color from universities and positions of status within society. Under Spanish rule, prestige and social status were associated with whiteness, and rights and privileges were, likewise, limited to those of lighter skin. Indeed, historian Marixa Lasso demonstrates that those who could not claim white and legitimate status were denied access to education and political rights.4 Things began to change with the Bourbon reforms in the eighteenth-century, when, seeking to revitalize the Spanish Empire, the monarchs and other imperial administrators created avenues for pardo (people of mixed white and black ancestry) inclusion. In 1778, for example, a royal decree created the pardo militias, thus giving people of color a chance to acquire social status through military service. A few years later, in 1795, another decree regularized an already-existing practice: the gracias a sacar, or royal waivers, a means through which pardos could obtain the same legal privileges as whites in exchange for service to the crown and a monetary “donation.” 5

Creole elites responded to such reforms with concern. Cartagena’s cabildo (a local institution of government, similar to a town hall), for instance, petitioned against the 1795 law that allowed the creation of pardo militias. They were not only unhappy with the prospect of widening the social spectrum to include non-whites, but also afraid that arming people of color and former slaves could lead to armed rebellions. The Haitian Revolution significantly contributed to this fear. As slaves in the former colony of Saint-Domingue rose up and destroyed slavery and colonialism simultaneously, creole elites and colonial officials across the Atlantic world saw slave revolts and race wars as a terrifying possibility.6 In Colombia, these tensions reached their height once the fights for independence began, because both the liberals (who were fighting for independence) and the royalists (who fought to preserve the monarchy) felt the need to attract the support of non-whites in order to win the war—or, in other words, to arm them.7 Indeed, slaves and free people of color actively participated in Colombia’s wars of independence, either fighting alongside liberal rebels or defending the Spanish king. One of the strategies employed by independence advocates to guarantee non-white support for their cause was to commit to the idea that a free republic would entail racial equality. This “myth of racial harmony,” as Marixa Lasso calls it, created a discourse that linked national identity to racial integration and equality. And yet, once independence was achieved in 1819, a large percentage of the non-white population remained excluded from the nation. The 1832 Constitution counted only free men as citizens and Slavery was not abolished in Colombia until 1851.8

This continued civil and political exclusion during the independence era significantly affected national memory and history as well. Traditional narratives of nation building largely disregarded the contributions made by people of African-descent and indigenous populations. For instance, the very first history of Colombia’s wars of independence, written by one of its protagonists (and Bolívar’s minister of the interior), José Manuel Restrepo, attested to the presence of non-whites in the struggles, but attributed their participation as motivated by money and alcohol rather than politics.9 This kind of interpretation that largely denigrated people of color was widespread not only in Colombia, but in most Latin American countries throughout the nineteenth century. In forging a national history after independence, most republics in the Americas adopted a positivist trope that emphasized great men and their deeds. The rise of positivism and other ideas of progress associated with whiteness in the late nineteenth century led not only to the dissemination of national histories centered around (white creole) heroes, but also to pessimistic assessments regarding the future. In Colombia in the early twentieth century, intellectuals and politicians saw the massive non-white population as a barrier to the country’s development and prosperity.

All of these factors led to yet another form of exclusion: exclusion from scholarship. According to Peter Wade, the myth of racial democracy was so powerful and pervasive in Colombia that for decades, studies of blacks in the country were relegated to the fields of ethnohistory and anthropology.10 Such studies tended to be either folkloric, or based on the criminal anthropology theories of Cesare Lombroso,11 highly influential at the time. It was not until the 1960s that the field of black studies experienced a real shift in Colombia, when a generation of black intellectuals began to change the discourse. In the 1970s and 1980s, several black organizations and associations appeared in Colombia and began pressing for change.12 This movement did not emerge in a vacuum: during those decades, the country faced social and political unrest as the population expressed awareness and discontent about the myth of racial democracy’s limits, and multiple guerrilla groups fought for opposing political projects. It was not until the end of the 1980s that several guerrillas agreed to put down arms in exchange for reinsertion into civil society.13 Elected in 1989, President César Gaviria took office in 1990 with the promise to call for a referendum, and that year the people of Colombia voted for a Constitutional reform. Elections to the Constituent Assembly were held, and the commission began work.14 In 1991, Colombia issued a new constitution, and article 7 of the new charter declared Colombia as a plural-ethnic and multicultural nation.15

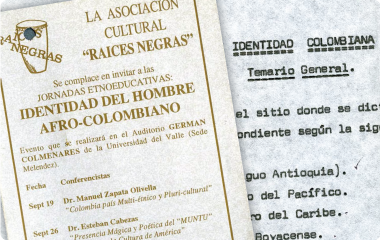

Civil society played a significant role in this constitutional change, and black and indigenous leadership were essential in inscribing non-whites into the charter.16 Manuel Zapata Olivella contributed greatly to this change, with his intense campaign to promote Afro-Hispanic culture in Colombia in particular, and in Latin America as a whole.17 In all of his work, be it at the Fundación de Investigaciones Folklóricas, which he founded and directed, at the Congress of Black Culture in the Americas, or through novels such as Changó, el gran putas (1983), Zapata Olivella sought to highlight the contributions made by people of African-descent.18 He recognized, however, that black contributions in Colombia (and in fact in the Americas as a whole) should not be limited to what existed in documents, especially because he was aware of their exclusion from memory, history, and scholarship. Zapata Olivella believed that oral history was a repository for the philosophy, behavior, and ideas of the oppressed, and thus a particularly relevant means through which to record and publicize black contributions.19 This belief motivated the project Voz de los Abuelos, which Zapata Olivella developed in cooperation with the Colombian Ministry of Education. The project dictated that, in order to graduate, high school students should conduct interviews with the elderly—the abuelos, or grandparents in Spanish—,often times illiterate members of their communities whose memories spoke to a variety of themes relating to Afro-Colombian practices and beliefs. Following the constitutional reform in 1991, Zapata Olivella designed an educational resource that sought to inform Colombians about their African roots and promote Afro-Colombian culture: the Enciclopedia Audiovisual de la Identidad Colombiana. This resource, developed by his Fundación, consisted of didactic materials such as tapes, pictures, slides, and texts exploring topics related to Colombia’s identity and history. The Enciclopedia Audiovisual could be purchased by schools and other governmental organizations to instruct students or workers; there was also a version for radio broadcast and a lecture series that Zapata Olivella offered in his efforts to reach as many people as possible.

Political reform and black activism have gone a long way toward improving Afro-Colombian realities. But contemporary Colombia is far from being an actual multicultural nation. Despite positive reforms achieved in 1991, some of the promises made in the charter are yet to be implemented. For example, the establishment of a National Development Plan for black communities remains on paper only due to budgetary issues.20 Similarly, in 1993, legislation designated collective ownership of ancestral lands for black communities in the Colombian Pacific, but has thus far transferred land titles of only half of the area that the project encompasses.21 In addition, violence and armed conflicts have displaced local communities, forcing internal migration processes that have affected the daily lives of thousands of Colombians—especially on the Pacific coast. Some of the black communities who had secured their communal lands through the 1993 law were forced to leave due to armed guerrilla violence; others, who were in the process of petitioning for land titles, had to abandon their projects for the same reason. Violence, according to Carlos Agudelo, has killed several black leaders, and black organizations have been left without guidance.22 While the government seems optimistic about pacification, crime rates remain high. As in many parts of the Americas, Colombia’s black population suffers the consequences of the never-ending nation-building process.

1 Richard Graham, ed., The Idea of Race in Latin America, 1870-1940, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990); Peter Wade, Race and Ethnicity in Latin America, (London: Pluto Press, 1997).

2 The 2005 census shows that 10.5% of Colombia’s population is black.

3 Data on the slave trade can be found in: Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (http://www.slavevoyages.org/). For the early slave trade in Cartagena, see David Wheat, “The First Great Waves: African Provenance Zones for the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Cartagena de Índias, 1570-1640.” The Journal of African History 52:1 (2011): 1-22.

4 Marixa Lasso, Myths of Harmony: Race and Republicanism in the Age of Revolution, Colombia, 1795-1831, (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007), 19.

5 Ibid., 20.

6 Ibid., 28. See also: David Geggus, ed., The Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World, (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001). The classic work on the Haitian Revolution is C.L.R. James’ The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, (New York: Vintage Books, 1963). A more recent analysis is in Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004).

7 Slaves and free people of color participated in the wars of independence all across the Americas. For an overview of slave participation in the Spanish American revolutions, see Peter Blanchard, Under the Flags of Freedom: Slave Soldiers and the Wars of Independence in Spanish South America, (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008).

8 Lasso, Myths of Harmony… especially Chapter 3, “A Republican Myth of Racial Harmony;” Jaime Arocha Rodríguez, “Los Negros y la nueva constitución colombiana de 1991,” América Negra 3 (1992): 39-56; David Bushnell, The Making of Modern Colombia: A Nation in Spite of Itself, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993); Peter Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture: The Dynamics of Racial Identity in Colombia, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993).

9 Lasso, 2. See José Manuel Restrepo, Diario político y militar: Memorias sobre los sucesos importantes de la época para servir a la historia de la Revolución de Colombia y de la Nueva Granada, desde 1819 para adelante, (Bogotá: Dirección de Información y Propaganda, 1954 [1886]).

10 Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture…, 3.

11 Cesare Lombroso, Crime, its causes and remedies, (Translation by Henry Horton, New York: Legal lassics Library, 1994 [1911])

12 Peter Wade, “Definiendo la negridad en Colombia,” in Estudios afrocolombianos hoy: aportes a un campo interdisciplinario, ed. Eduardo Restrepo (Popayán: Editorial Universidad del Cauca, 2013), 21-37; Carlos Agudelo, “La Constitución política de 1991 y la inclusión ambigua de las poblaciones negras,” in Utopía para los excluídos: El multiculturalismo en África y América Latina, ed. Jaime Arocha (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, 2004), 179-203.

13 Arocha, “Los Negros y la nueva constitución….”.

14 Ibid., 44.

15 Ibid., 49; Wade,“Definiendo la negridad en Colombia,” 26; Agudelo, 184-194.

16 Arocha, “Los Negros y la nueva constitución….,” 39-40; Wade, “Definiendo la negridad en Colombia,” 26-29.

17 María Vivero Vigoya, “Mestizaje, trietnicidad e identidad negra en la obra de Manuel Zapata Olivella,” in Estudios afrocolombianos hoy: aportes a un campo interdisciplinario, ed. Eduardo Restrepo (Popayán: Editorial Universidad del Cauca, 2013), 87-101.

18 Manuel Zapata Olivella, Changó, el gran putas, (Bogotá: Rey Andes Ltda., 1992).

19 Manuel Zapata Olivella, “La tradición oral, una historia que no envejece,” in El negro en la historia de Colombia: fuentes escritas y orales, (Bogotá: Fondo Interamericano de Publicaciones de la Cultura Negra de las Américas; UNESCO; F.C.I.F., n.d.).

20 Agudelo, “La Constitución política de 1991…,”194.

21 Ibid., 194-196.

22 Ibid., 197-198.